It all starts with art...

My very dear friend,

In my last journal entry, I spoke briefly about the house my partner and I had just purchased.

I live in Montreal, Canada. As with much of the country, the bulk of our cities were largely constructed from the 1950s onwards. There are the old towns, sure, those century-old homes that either housed workers, in the lower parts of the city or, on higher grounds, the bourgeois and the small gentry, both of which are now worth something of a small fortune, but the bulk of homes wee now live were largely built in the last 70 years.

Montreal is a collection of small villages slowly grafted onto one another as their population grew. Before 1950, our neighbourhood was one of the villages, something of a tiny suburb to the city and, on the site where we now live, there was nothing but a great big open field and a very small barn.

As Montreal’s population grew and housing needs increased, buildings started springing up left and right, the field was acquired by a developer who built dozens of homes, each going for less than $50,000 apiece. Had you told me a year or two ago that I would come to purchase a 1950s “box” home, I would certainly have laughed you out of the room. This home, however, has a garden and the rooms are large and so are the windows - so my dreams were realised, once again, in a way I could not have imagined. Admittedly, much work will have to be done to bring it into the modern century (a journey I will take you on!), but it has good bones and great potential. It is a unique sort of privilege (and therefore of responsibility) to take care of a home that was there long before you and will (hopefully) stand much after you are gone.

While I love the cottage aesthetic and all of my heart races to that very English style, there is a certain form of integrity and respect for the history and fundamental style of a house that one has to exercise when thinking about renovations and decorating. This is not a cottage, but a 1950s oddly semi-suburban urban home and I, as her caretaker for the time being, hope to honour her character.

Last March, my partner and I were in Paris for a few short days that were spent, for the most part, immersed the wonderful world that is Hôtel Drouot, a Parisian establishment of the auction scene. Here, you can find anything from the typical brocante on the lower levels to high-browed art and antique sales on the upper floors. Better than a museum, you can browse through 16th-century chairs (and try them for comfort if you so wish), come so close with original Vermeer, Matisse and Renoir paintings that you could almost imagine them sitting proudly in your own sitting room, try on emerald and gold and diamond jewellery pieces and bid on works by artists of all notoriety. We did try our hand (albeit rather shyly) at a bid on a bright and joyful portrait by Maurice de Becque, illustrator for Rudyard Kipling’s The Jungle Book. We had spent the prior hour notebook in hand, calculating conversion rates, auction fees and shipment costs only to find that it all amounted rather quickly to a significant sum of money. Our bid, perhaps unsurprisingly, was outdone. The experience, however, lit something of a fire beneath us and we spent the remainder of our time scouting out the City of Lights’ many smaller galleries.

One early afternoon we stumbled upon a tiny little space in a corner tucked away from Montmartre’s hustle and bustle. There, we spent hours with the gallery owner, perusing through lithographs produced by the greats of Mid-Century Paris - Matisse, Chagal, Braque, Picasso and of course, Miró. Aurélie was friends with Eric Mourlot, grandson of Fernand Mourlot who had set up a print shop frequently visited by the greats of the day on rue Chabrol, seeking, at the height of the century, for new ways and new techniques to craft, and paint and experiment with artistic form.

From that afternoon spent wandering down the rich paths of Paris’ vibrant artistic legacy, we came away with an artist proof of a poster designed by Joan Miró for a late 1960’s exhibition. We were drawn to its colours, to its movement and to its name, Le lézard aux plumes d’or. It reminded us of some lively jazz piece, made for singing and laughing and dancing.

Miró was always known for his use of colour and for his love of his native Catalonia. I imagine him as something of a quiet character. Born into a family of goldsmiths and watchmakers, he had both pursued studies in business and art, worked shortly as a clerk, a venture which drove him sick and set him off on the definite path to pursuing life as a painter. Unlike many of the other artistic personages of the time, Miró had his feet firmly planted on the ground and did not particularly pride himself in exhibiting extravagant bouts of eccentricity. He painted (and later experimented with different forms of creation), simply because, deep down, he knew that was the only thing he wanted to do.

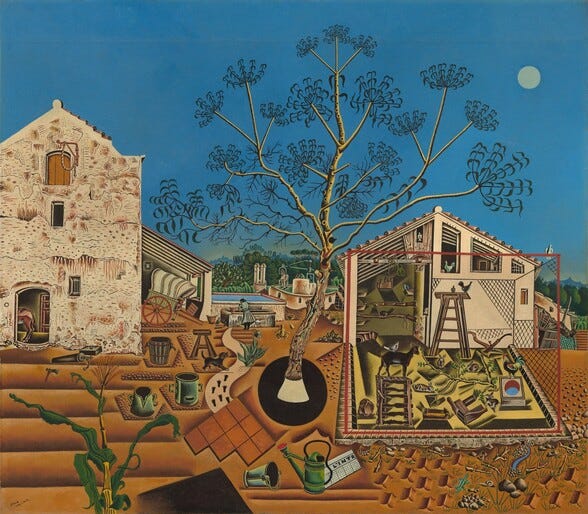

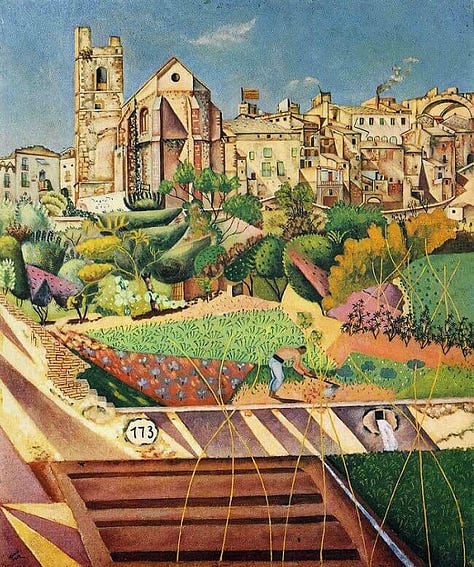

Miró’s first pieces are tributary to the fauvism & cubism movements, whereby the artist refuses the realistic representation of nature and instead makes use of colour and form to distill the very essence of the reality that lies before him. One of his early painting, “The Farm”, a depiction of his grandparents’ property in the Catalonian hills, was purchased by Ernest Hemingway, who, having acquired it by the seat of his pants, notoriously praise it for having in it “all that you feel about Spain when you are there and all that you feel when you are away and cannot go there.” Such was the degree of concentration, observation and pure, almost childlike love, that Miró poured into his work.

In 1920, Miró moved to Paris where he became increasingly acquainted with members of the Surrealist movement - Max Ernst, Dalí, Magritte,...- and while he says he never officially joined, he became more and more interested in symbolism, automatism and the relationship between the conscious, the unconscious and the subconscious mind. He pursued his work in quest of colour and form, until the reality of the subject became eclipsed (or perhaps revealed) by abstract swathes of vivid blues and reds and yellows and blacks and touches of greens.

To me, Miró’s work evokes the movement, the colour and the music of a life distilled down to its very essence - shapes and forms, light and shadow - some lively jazz piece made for singing and laughing and dancing and crying, sometimes too.

Created in the late 1960s, during the last decade and a bit of Miró’s life, Le lézard aux plumes d’or, The gold-winged lizard, may be the foundational piece I am drawing upon for this home - simple, vibrant, alive with the burning desire to distill the reality about us and see it born anew in novel, imaginative and fantastic forms.

This, I hope, will be a home for the arts and that wonderful ebullience of creativity in all its forms…

xxx

Camille